Jack O’Connell / Resurrectionist Week: O’Connell on His “Baptism”

Late spring, 1969: John and Yoko stage a bed-in for peace in Montreal. Warren Burger becomes Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Hee Haw premiers on American television. And back in wormtown, as the weather turns warm, my obsession with the space program begins to reach fever pitch. I’ve spent the last year memorizing details of the Mercury, Gemini, and (the first 10) Apollo Project missions. I know the names and the positions of all the crews in the same obsessive manner with which my buddies know the batting average of Yaz or the ERA of Jim Lonborg. The walls of my bedroom are covered with the fold-out posters from the Doubleday mail-order Science Service club—all those wonderful maroon boxes containing pamphlets and maps and cards and whatnot. I am embarrassingly proud that my city’s David Clark Co. produces the astronauts’ pressurized suits. Jules Bergman is my lifeline to NASA. And when I discover that Robert Goddard, the father of modern rocketry, was born in my hometown and fired the first liquid-fueled rocket just eight miles from my house (and—can it be possible?—that my family’s encyclopedia set is housed in one of Goddard’s own bookcases, purchased from the widow after the great man’s death), my head comes near exploding from the immensity of the pure geekity excitement ricocheting around in the melon.

It is at this moment, in the waning hours of the fourth grade, that the latest issue of Our Weekly Reader arrives one Friday afternoon. Sr. Mary Charles waits until the end of the day to distribute our copies, which, upon receipt, I discover, contains a book-order supplement. I walk home wondering if the pulpy little supplement might offer another Peanuts or Andy Capp or Wizard of Id cartoon collection. Wondering which paperback will claim my hard-earned 50 cents. But when I enter my bedroom and spread out the supplement on my gunmetal desk, my eyes lock, at once, onto a different offering. And refuse to budge.

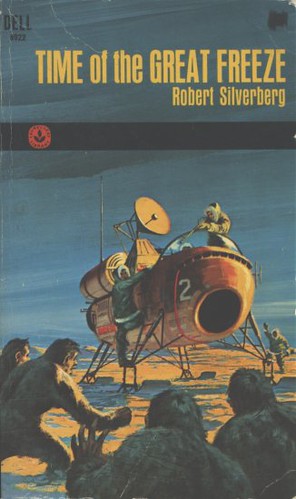

Maybe it’s the cover art—though the reproduction is tiny and printed in black & white. Maybe it’s the thumbnail plot description, which sounds terrifically exciting. Maybe it’s the title itself: Time of the Great Freeze. But in the moment that I fixate on this little novel, I know I need look no further. I have found my selection. In addition, I know I’m done with cartoon books. And beyond this, I understand that I need to memorize the author’s name: Robert Silverberg.

I fill out the order form. I find two quarters in the desk’s middle drawer and scotch tape them to the form. I place form and taped coins in an envelope and place it, like a holy relic, in the center of my desk. And for the rest of the afternoon and evening, I try to ignore the current of electricity vibrating along my spine.

The next day, I turn in the envelope to Sr. Mary Charles.

And then, the waiting begins.

While the rest of my classmates are bemoaning the slow grind of days until summer vacation, I’m scared to death that the school year will end before our last book order of the semester arrives.

But arrive it does, at long last.

In my memory, it is the very last day of my fourth grade year. At some point in the morning, the principal arrives in our classroom to deliver a brown shipping box to our teacher. My heart thumps. My head throbs. I know it contains the books.

Sr. Mary Charles thanks the principal, eyes the box for a moment … and then places it on the windowsill and returns to the day’s lesson.

I spend the next five hours staring at that box. It’s June and the heat outside causes my vision to blur, the air to waffle and waver.

Finally, about 15 minutes before dismissal, Sister finishes up some exercises and moves to the windowsill to retrieve the book box. She brings it to her desk, places it in the center of her blotter, withdraws scissors from a soup can pencil cup, and, slowly, inexpertly, slices the taped seals of the package.

She withdraws the class’s master order sheet and begins to hand out the various literary purchases of her students. And I am on the edge of my seat. I am sweating. My nerves are clenching and my teeth, grinding. I am, in fact, an addict in miniature. (Years later, reading an anecdote about Cheever or Carver leaping from a still rolling car into the parking lot of a just-opening Iowa City liquor store, I thought, oddly but tellingly, of my wildly over-the-top impatience on that day in fourth grade.)

Now the box is almost empty. I am, of course, the last to receive my treasure. That’s the way these stories work. Mr. Silverberg would understand.

But suddenly, Sister stops the distribution. She freezes in mid-dispersal and removes hand from box. And I know something is wrong.

I watch her bring the order form up closer to her eyes, then peer down into the depths of the shipping package. And then, with a look of confusion or annoyance, she says, “Oh, no. We seem to have a problem.â€

My stomach seizes up a little.

“Mr. O’Connell,†she says, and I lift my face.

“Miss Nicholson,†she says, and my head pivots to find the classmate whose name has been called in conjunction with my own.

“You both ordered the same book,†Sister says, re-consulting the form. “But they only sent one copy.â€

I am suddenly terrified that, as in the Solomon story we learned this year, Mr. Silverberg’s beautiful, slender paperback might be hacked in two.

I should have known better. Like virtually all of the nuns I had come to know since kindergarten, Sr. Mary Charles loved and respected books and reading. Hadn’t our “reward†for promptly finished work been a trip to the black wire bookstand at the front of the classroom, and the time to read freely in whatever selection we chose from the class ‘library�

In addition—and also like all the nuns before her—she was a pragmatist. And so, glancing at the clock above the chalkboard, she said, “Pick a number.â€

Mary Kate and I looked at one another.

“Quickly,†Sister said. “Pick a number between 1 and 10. Whoever guesses the correct number first will receive the book. The other gets a refund.â€

A protest started to form somewhere in my throat. But before it could surface, Mary Kate said, “Six.â€

And before I knew what I was doing, as if someone had pushed a button in the back of my neck, I shouted, “Eight.â€

“Eight it is,†Sister said and handed me Time of the Great Freeze.

Do I believe I really guessed the right number on my first attempt?

Pointedly, yes. The universe wanted me to have that book. And it wanted me to know just how much I desired the novel.

In memory, the dismissal bell then sounds. Miss Nicholson approaches the big desk to settle up with Sister. I exit the school with the holy artifact in my hands. And a sense that my life is, somehow, about to change.

And I’m right.

Over the course of that night and the next day, I read the book in crazed, hungry gulps. I have been a reader from the beginning. I received my mother’s obsessive love of the narrative and the physical text. But I’ve never been captured so thoroughly by any book before. Maybe it’s the subterranean setting of the early chapters—I already have a weird thing for underground imagery. Maybe it’s the oppressive, totalitarian government against which our young hero must battle. Maybe it’s Mr. Silverberg’s masterful ability to create pace, suspense, engaging and sympathetic characters. It’s likely all of these things, adding together to create my first episode of living within a genuine moment of wonder.

Simply put, this Silverberg kidnapped me. And my 48 hours in captivity changed me forever. Silverberg initiated me. Baptized me. Made me a part of what I would slowly come to understand was a tribe of likeminded wonder kids.

(To this day I entertain a fantasy of flying to his digs in the Oakland hills and laying a bottle of great single malt and some kind of reverential flowers at his door. I’d never actually ring the bell, of course—I’m way too superstitious to gaze on his visage.)

Nothing, as they say, was the same after that. I’d wager that a lot of you reading this have read Time of the Great Freeze. I’m betting that Silverberg initiated a lot of us. But if it wasn’t Mr. S that kidnapped you, perhaps it was Mr. Heinlein. Or Mr. Bradbury. Or Mr. Ellison. Or Mr. Leiber. In one sense—in this specific regard—they’re all the same person. They’re the visionary who was sent to remake you at that exact moment when you required remaking.

About a month after my initial reading of Freeze (I read it three or four more times over the course of the summer), Armstrong and Aldrin landed on the moon. My father let me stay up until the small hours, sitting with me on the couch, staring at those fuzzy, impossible pictures of men in bulky white, bouncing through craters. I was beside myself with excitement, with a dash of fear—and, I think, with pride.

But, to take nothing away from those astronauts or that momentous, majestic undertaking, the truth is that my sense of sublime, ecstatic wonder had already been apprehended. In the moment when I fell, utterly, into a fabulous adventure tale by Robert Silverberg. And was launched forever out of the land of the mundane. —Jack O’Connell

5 comments on “Jack O’Connell / Resurrectionist Week: O’Connell on His “Baptism””

I love stories like this.

And you’re right – a lot of people will have their own moment of baptism. Different time, different place, different book, but I’m sure that, just like me, they read this post with a big ol’ smile on their face.

You got that right! My own baptism was Andre Norton’s Galactic Derelict. Hell, I didn’t even know what those words meant! But it changed my entire life: made me a reader. I don’t know how many times I’ve read that book over the last 45 years, but it doesn’t matter. It’s always the same, always wonder-filled. And I can still see the spine of the novel, inevitable on the junior high library’s shelves. I always will see it and remember that moment, its smell and clarity. Cool. Great post.

Like probably everyone here, I was an early reader. And the writers I read first as a kid were Martin Caidin, Willy Ley, and Fletcher Pratt, all of whom were writing non-fiction about why it was important for the human race to move into space, and how it could be done. They all mentioned this thing called “science fiction.”

My Dad went to Vietnam in late 1961, and my Mom and I (no brothers or sisters) moved for the duration to her hometown of New Lexington, Ohio, population 5,000, where I completed first grade and went through second. The only science fiction I read during those early-reading years was the “Mike Mars†series about a USAF astronaut (written by Donald Wolheim). I wasn’t fully aware that that was what it was.

Dad returned in November 1963 and we moved to Dayton, Ohio, to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Before we could move into our permanent quarters, we lived for two weeks in “Wood City,†where the barracks for enlisted personnel were.

That’s where the base library was, too.

I decided to try to take a look at this “science fiction†stuff I’d heard about. There wasn’t a “kids section†of the library like there might be at a regular public library, so the first sf book I ever checked out and read ended up being Asimov’s /I, Robot/.

There was no going back. I was hooked. The first one was free, little boy…

I LOVED this book, and also purchased it through the Scholastic Book Club in third or fourth grade. I have a copy on my bookshelf today, thanks to eBay. Thanks for bringing back the memories.

Did poor Mary Kate ever get her book? Did you loan her your copy? (I was hoping this story might end up with you two married or something.)

Comments are closed.