Editing Fiction Anthologies (Part 1)

Although I am posting this entry to my blog, my wife, Ann VanderMeer, contributed significantly to the content and wording. See also the previous posts Anthologies: Comments, Anthologies from a Reader’s POV, and Anthologies from a Writer’s POV. – JeffV

Editing original anthologies in the twenty-first century has become much more than a process by which you skillfully put 10 to 25 stories between two slabs of pulped wood and glue it all together. I think you can chart the beginning of the changes from the 1970s, a time when, if you look at many of the anthologies being published, they didn’t so much pitch readers on the names of authors as on themes or a series or editor’s brand. But at some point, this wonderfully ego-less approach went away, and over time the creation of an anthology, especially at the commercial publisher level, became more name-driven, and thus a little more like a Hollywood pitch.

That said, acquiring a core of well-known/best-selling writers for your anthology project most definitely isn’t “selling outâ€â€”those authors are in that position because they’re professionals who have produced great fiction for either a general or strong niche audience for a number of years. They are known for bringing a particular style or approach, and a certain level of quality, to whatever they do. Invites to these writers should be based on genuine affection for and appreciation of their work, along with knowing they’re right for a particular project.

However, this part of the process also shouldn’t devolve into a reflexive seeking out of the same core group for each anthology. There is an impulse—quite normal and understandable—on the part of agents and editors to want the same handful of names as the Holy Grail for an anthology. In actual fact, though, those particular writers only contribute to a tiny percentage of anthologies each year—and Fantasy & Science Fiction is actually wide and deep enough for other names to have impact as well. (it’s worth noting that Indie press anthologies are not immune from needing established writers, either—sometimes it is even more important given the vagaries of distribution and getting the word out.)

Within this paradigm, there should still be plenty of room for inviting less commercial writers and newer writers to participate in your anthology. Indeed, we would argue that as an editor you have a responsibility to the health not only of your anthology but of the SF/Fantasy community (or whatever genre you’re working in) to encourage submissions from newer writers. It is becoming increasingly clear, too, that, a narrowness in reading tastes can be an active liability, given an increasingly omnivorous readership.

The advantage of experience does often result in greater consistency from an established writer. However, it is not true that established writers will automatically produce better work. One of the unfortunate byproducts of the otherwise often wonderful S/F subculture (or any subculture, really) is a fixation on personalities and types that sometimes obscures the actual work and supports an unspoken assumption that X, Y, and Z are “hot†and therefore more talented than A, B, and C. An editor’s ability to at times ignore the shiny-shiny and the hype that lubricates the genre community is essential to producing quality anthologies.

As alluded to above, another important element is knowing what writers are best for which projects—and which aren’t. Sometimes this means playing to a writer’s perceived strengths. Sometimes it means having the insight to invite them to a project that seems counter-intuitive given their skill set or focus. Asking a writer to play against type requires careful research on the part of the editor, along with a kind of gut feeling based on experience that this is the right decision. The reward? Asking a writer to do something different from their usual approach can translate into a certain freshness in the writing of a story, and thus result in great fun for the reader.

At any given time, Ann and I have lists of upwards of 200 writers who might or might not be right for a given project. Sometimes it takes awhile to get to a project or point where we can invite a particular writer, for any number of reasons. Recently, a writer, somewhat against their own instincts, asked why they hadn’t been invited to a project. Ironically, in another few months we indeed would have been inviting that writer to a project. In fact, when we have open reading periods, we often flag the names of writers who seem talented but whose work wasn’t right for the particular anthology—and come back to them with encouragement when we do have a suitable project. Beginning writers in particular should recognize that submitting a story to editors who edit anthologies regularly is an audition that may pay off much later.

There truly are actually many more writers out there with the skills and talent to write for any given anthology than you can possibly use. This is one reason why seeing the same names again and again in anthologies sometimes strikes us as odd. Editors will always have favorites and favorite modes of writing, but it also behooves editors for their own self-improvement and continued learning to expand the scope of their reading and research on an ongoing basis. In our case, we are aided by doing projects jointly and having reading tastes that intersect but are also independent on one another. We are omnivorous, and read widely outside of core genre. We are also constantly in seek-and-explore mode. The point of this branching out and forward movement is to try to avoid stasis, for the health of our projects and our own personal edification and growth (which also impacts my writing favorably). You always have a blind spot, you always make mistakes, and we don’t mean to pat ourselves on the back for something that is part of an organic inquisitiveness…but as an editor you can either make yourself less or more receptive to new things.

So in that context, we try hard to mix it up as much as possible. All things being equal, and an editor’s reading being wide and deep, there is no real constraint today against producing anthologies that are various as to the experience level of the writer, the background of the writer, and the approach of the writer. This isn’t about creating quotas of any kind, but about encouraging access to projects and using one’s leverage to nurture as many interesting approaches as possible—which enriches not only whatever project you’re working on now but projects in the future. (It’s worth noting, too, that over the past five years there’s been a huge uptick in the number of non-Anglo writers entering the field and finding an audience; it would be a little odd for that not to begin to influencing anthology table of contents.)

Factored into this equation is simply who best fits the project at hand, along with who is available and who is interested when contacted—elements that advocacy and outreach can help correct for if you find yourself getting a lot of “no thanksâ€. Certainly, though, there are situations beyond your control or types of projects for which you may not be able to attract as much variety as you might wish—for example, for a reprint anthology, a limitation imposed by, for example, the composition of writers associated with a particular literary movement.

A pet peeve related to including diverse approaches is the artificial divide between “genre†and “mainstream†or “genre†and “literary,†in part because it separates like from like, especially with so much fantasy published by non-genre imprints these days. But also because it can blind an editor to wonderful writers simply because they aren’t part of the genre subculture. This blindness can result in less richness when inviting writers to an anthology. For reprint anthologies, it can also blind an editor to work published in translation from other countries, simply because a certain percentage of this material isn’t published within genre and therefore isn’t considered fantasy. Most of our anthologies have a subtext of healing this rift, of ignoring this barricade. There is an implicit desire, too, for writers who might otherwise rarely encounter one another’s work to enter into communication with one another. We have seen the results of not just indirect influence in this context but also the wonderful aspects of direct dialog between creators.

Part of this process is to hardwire the idea of taking chances into your general mission statement. We’ve always been a fan of Angela Carter’s statement that she always wanted her reach to exceed her grasp. We believe this is as important a concept to consider when editing anthologies as it is when writing fiction. You will fall on your face every once in awhile, but most of the time you’ll get much farther, with more reward, than if you’d been less ambitious. We all only have so many books in us, and only so much time in which to create them. Given a finite life and finite resources, it seems commonsense to focus on that which is unique and/or more personal whenever possible.

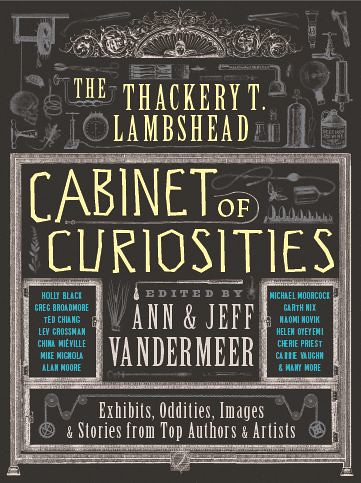

The second part of this two-part blog entry will focus on The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities and post later this week.

8 comments on “Editing Fiction Anthologies (Part 1)”

I agree. There are a few anthologists out there who have basically been putting out what looks to me to be the same book year after year. A few of the”best of” anthologies are like that also – the same group of writers in 2010 for example as they had in 2005.

Thanks for opening a door on how anthologies are created. I for one don’t see why adding big name authors to the TOC is called “selling out” (not that you do either, but I have heard such complaints from a few authors over the years). After all, big name authors are often big names precisely because they know how to tell a great story. But as a reader I also love anthologies which expose me to exciting authors I’d never heard of before. If an editor can mix big name authors with new ones, and provide me with a ton of great stories for a reasonable price, I’m hooked.

BTW, science fiction and fantasy lovers often mention the 1970s as a high tide for short story anthologies because, as you state, back then the anthologies focused less on big names and more on themes, series, or the editor’s brand. However, what many people forget is that so many mediocre anthologies were published during that decade that they eventually crashed the market, a situation which stunted the anthology market for decades.

Jason: I’m not entirely sure it’s because of the market crashing for that reason. Perhaps a factor, but all kinds of other things may have contributed.

Many of the older genre writers are pretty matter of fact about laying the blame on editors like Roger Elwood, who flooded the 1970’s anthology market with poor quality books. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Elwood#Market_flooding for more.

Of course, I’m sure there were other factors. And this in no way implies that today’s market is going through a similar boom of bad anthologies. I don’t see what happened in the 70s repeating itself.

Jason: I’m just saying that I find anecdotal evidence fairly unconvincing. It becomes a received wisdom, and I’d just first, for my own part, need to investigate further before I’d be willing to say it was *the* major factor.

Valid point. All I have is anecdotal evidence put forth by others. While the large number of anthologies coming out in such a short span does indicate the market became over-saturated, I’ll leave it to others to debate if that was truly the case.

And again, I’m not saying this is happening today. The book market today is totally different, as are the editors. I merely brought this up because the 1970s were an interesting time for SF anthologies. Apologies for derailing your thread with this.

It is some thing I need to find more information about, appreciation for the publish.

Jason: It may well be happening today. There’re certainly waaay to many effing zombie anthos out there.

Comments are closed.